Developed by:

Mg. Victoria Francisca Jiménez Martínez39

Dra.(C) Bernardita de los Ángeles Abarca Barboza40

Giulia Marzi Ragghianti41

Coordination and editing by:

Mg. Evelyn Aguilera Arce42

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), was a Spanish visual artist of great versatility who explored diverse plastic languages. His development as an artist begins early with his training in academic realism43.

.-photography.jpg) |

| Imagen 6.1. Pablo Picasso (1904). Photography: Ricard Canals i Llambí |

The development around its formal and chromatic experiments has as initial mark the stage known as blue period (1901-1904 approximately); this would have been triggered by the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas and is characterized by a cold chromatic range "and the melancholic a ”44.

In April of 1904 he settled definitively in Paris with important economic difficulties and in August of this same year he meets Fernande Olivier, his first couple. This year is a characteristic node of his career, because he begins the pink pictorial period (1904-1906), where produces a significant change in the use of color over the previous phase, "developing compositions with classic shapes and warmer colors, in which the characters leave the isolation of the previous phase"45. With Fernande Olivier, Picasso frequents the artistic surroundings of Paris, and that's how he makes friends with

Guillaume Apollinaire, André Salmon, Juan Gris, Marie Laurencin, Leo Stein46.

In 1906 he met Henri Matisse, who influenced the enrichment of his palette and the formal exploration, from African art. That same year he also met Georges Braque, who became a close friend and co-worker in the development of Cubism.

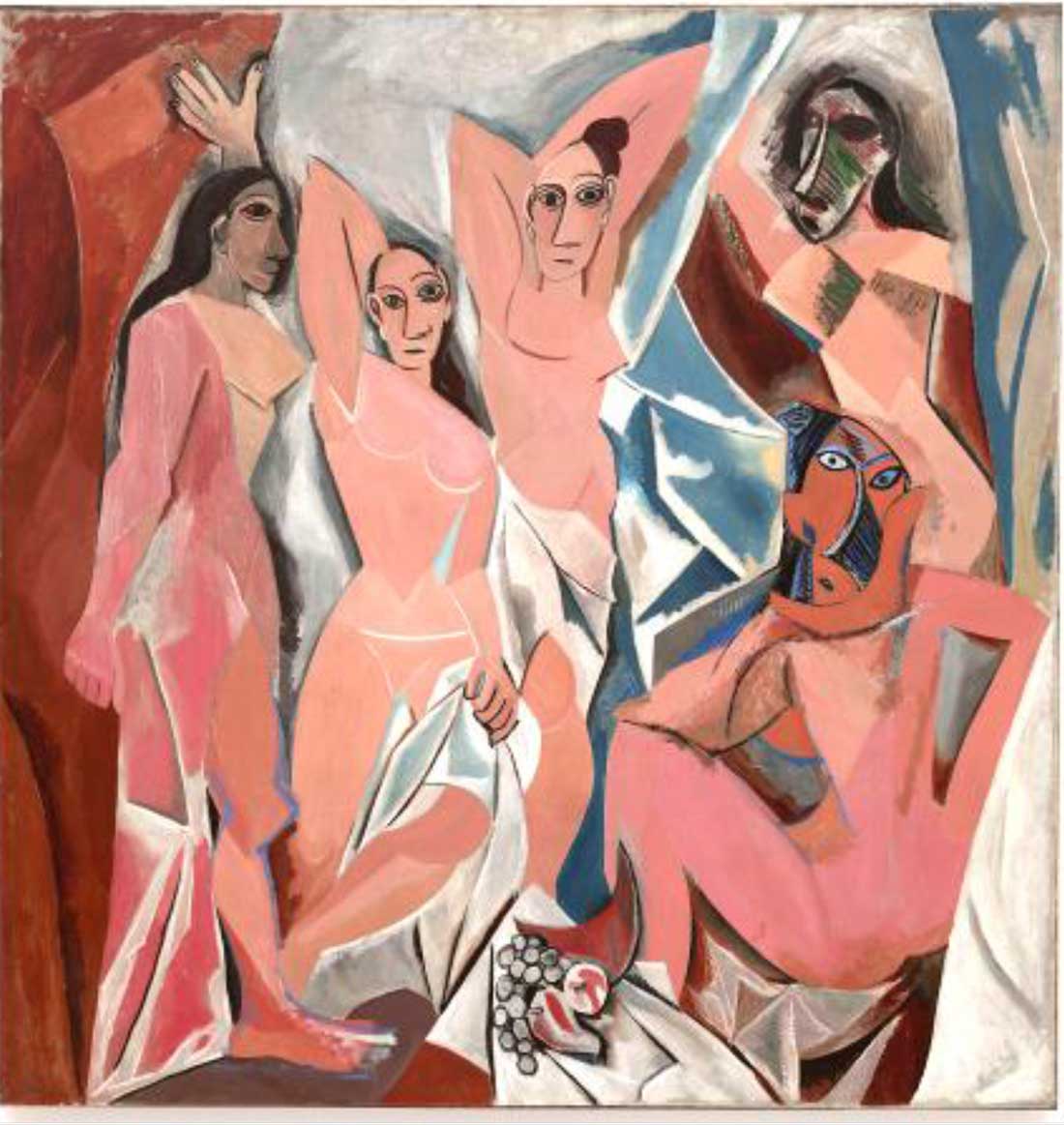

In 1907 he made Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, a work considered the origin of cubism by its relation between figure and background.

Image 6.2. Les demoiselles d'Avignon (1907)

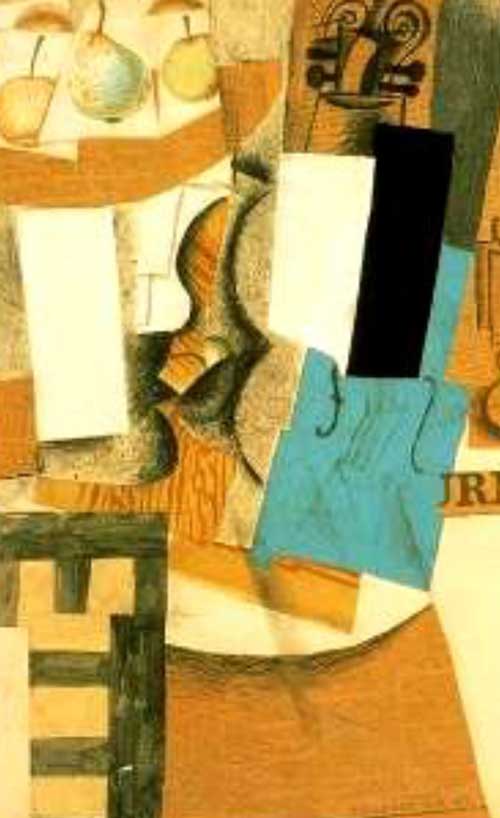

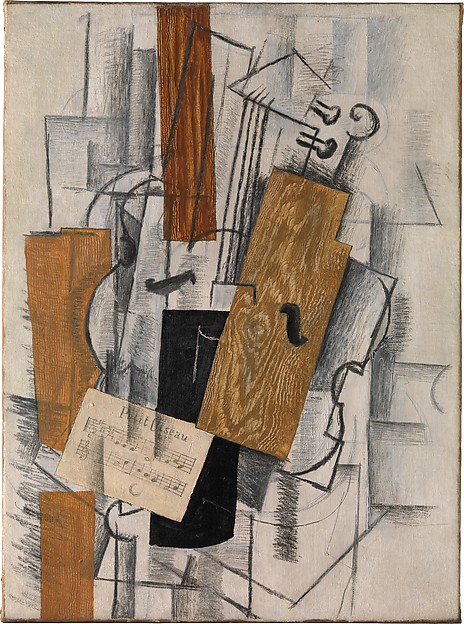

Both Picasso and Braque are involved in analytic cubism, which stretches from 1910 to 1912, period in which they are in charge of "setting up a new pictorial space, breaking with the illusionist perspective system established in the Renaissance and perpetuated for centuries"47. Then, by the year 1912, synthetic cubism would emerge, which unlike the previous period seeks to be more understandable to the viewer "synthesizing and diminishing the multiplicity of elements and facets of objects, which begin again to recover their reality and color"48 .

In 1914 World War I exploded and the French friends of Picasso go away to the war. As Spain is a neutral country in the conflict, Picasso is not recruited, however, some of his friends do not return and others are injured, such as Apollinaire, Who suffers a trepanation49 and Braque that suffers a serious injury of a slow recovery; Situation that leads him to resume his artistic work in the year 1917. This postponement of Braque, would have been one of the main reasons that would justify the dissolution of the intimate friendship between Braque and Picasso50.

In 1917 he joined Diaghilev's theater company, working on the decoration and costumes of the Parade ballet, a link that lasted until 1924, at that time he designed the decoration and costumes for the Mercure and Letrain Bleu ballets51. In this Russian ballet company he meets Olga Khokhlova, with whom he married in 1918, the same year that Picasso began to develop works of neoclassical character.

Subsequently he develops the theme of the bathers and focuses on his bullfighting works, which arise from his great passion for bulls and the symbolic link between this animal and Spain.

Towards the year 1936 paints the Guernica and from 1947 begins to realize ceramics.

Picasso maintains his artistic work for life, which always carries the stamp of his own experiences and experiences that include social themes, portraits, women sitting, erotic scenes, musical instruments, bulls, among others.

Some versions of the story argue that in Paris Picasso was surrounded by an environment in which music had an important presence. Some of her first friends in this city were Suzanne Bloch - who became a well-known singer - and her brother Henri Bloch, who was a violinist52.

Another Picasso friend linked to music was the painter Henri Rousseau who was known not only for his condition of painter, but also for violinist. Some versions of the story maintain that a distinctive aspect of Picasso's relationship with Rousseau was the consequence of a purchase that the artist from Malaga made to one of the works of the Frenchman in Montmarte, a portrait of a woman. This acquisition induces Picasso to celebrate such a purchase and honor Rousseau53. This instance was approached later, in the sixties by Manuel Blasco Alarcón, who immortalized in a painting this event: "they danced to the son of the accordion of Georges Braque and the violin of Rousseau himself, who played until the alba waltz and one of his own compositions"54.

This is how it is possible to see at different moments in the picassian history, the presence of musical instruments, where the string ones had more emphasis. Braque also approaches the instruments in his artistic creations; nevertheless, Picasso did it with a look towards the interpreter with the instrument. This creative harmony between them

led them to make inroads into the explorations of the other. In this dynamic of interaction, Picasso introduced violins in his works, as Braque used to do and the latter made some painting with instrumentalists, a frequent theme in Picasso. This exchange of concepts is evident in the framework of their relationship of friendship and work, especially when comparing these productions with their usual styles. In fact, Picasso, in the periods before cubism, used mandolins, guitars and tenors; Braque, for his part, performed still life with instruments55.

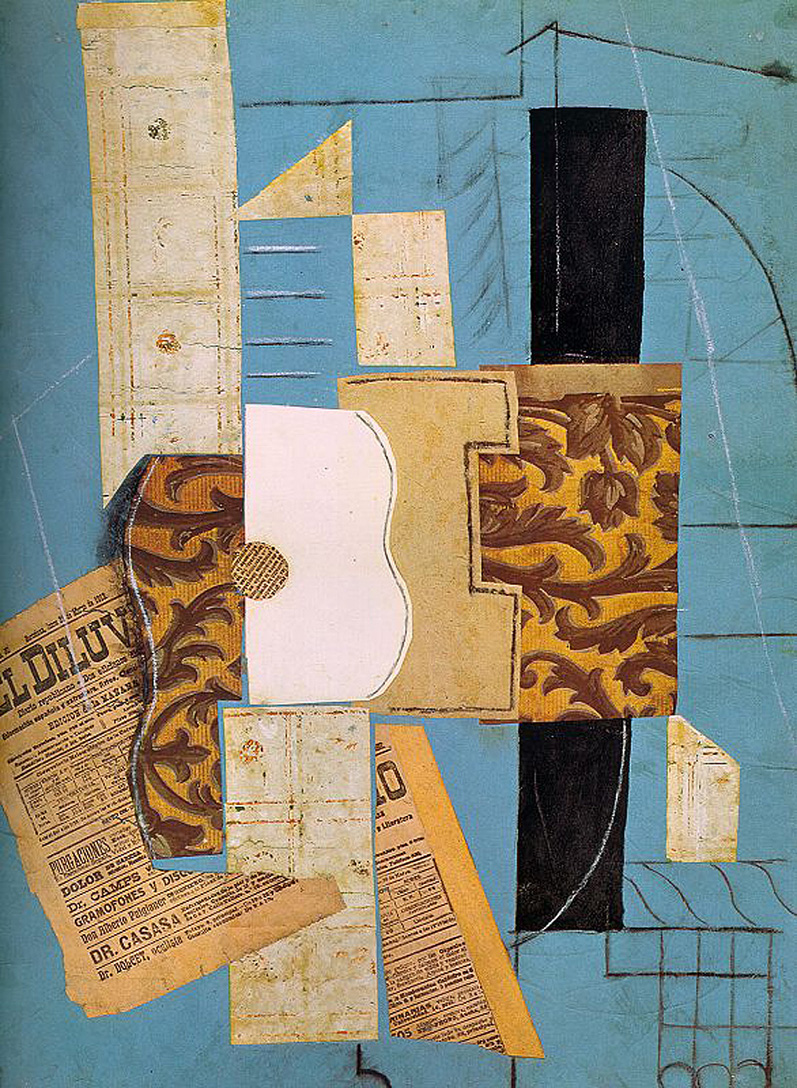

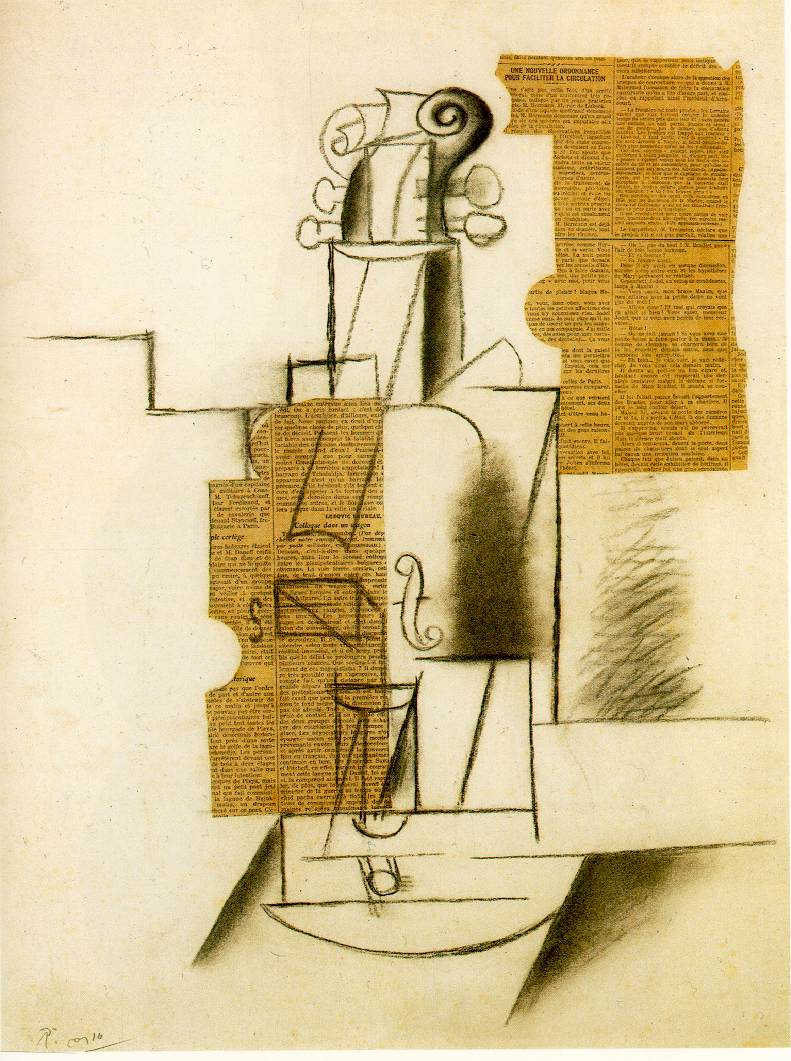

The presence of violins in Picasso's cubist works is numerous, between 1912 and 1913 appear in at least fourteen papiers collés. For Gary Tinterow and Susan Stein this may be because string instruments can be visually recognized from small and unmistakable details and their curves can be related to those of the human body56.

The decisive inclination towards the cubism takes place between 1906 and 1907. In these years the great retrospective is realized on the painting of Cézanne, who died shortly before, that influenced to Picasso. His interest in African sculpture arises, with Matisse introducing him to these expressions57. From this exotic primitivism that had fascinated the European artistic culture, from Gauguin onwards and the need to continue the experimentation that always characterized Picasso, in 1907 comes the work Les demoiselles d'Avignon, which is considered the beginning of the time Cubist of Picasso.

Since 1909 Picasso and Braque have been working closely together

(...) as the rope in the mountains, "Braque will say, thinking of our very different temperaments, we were guided by a common idea ... During these years we have said things between Picasso and me that no one will ever say things that nobody could be said, that nobody would be able to understand ... things that would be incompressible and such satisfaction have given us ... and this will end with us ... above all we were concentrated58.

Picasso and Braque, in the analytic phase of cubism, produced works that could not be recognized from among them the artist who created them, an example of which are Picasso's Poet (1911) and Braque's Man with Guitar (1911). Together they investigated the "new space" maintaining cubism in its primitive rigor.

The cubist phase was a stage of great experimentation, in which Picasso put into question the very concept of artistic representation. In the first cubism, called analytic, the object that loses the real form is decomposed, not recognizable, are detailed facets that come to show the object in multiple aspects, representation is almost graphic annotation only, reproducing pure architectural volumes losing readability . Picasso was interested in the simplification of the form, arriving at a pure sign that contained in itself the structure of the thing and its conceptual identification.

The cubist collage is invented in a context which is contradictory: "the continuity of the inspiration of Symbolist poetry, the rise of popular culture and protests against the war in the Balkans"59. Picasso and Eva Gouel, the artist's second companion and inspirational muse, spend the summer of 1912 in a village near Avignon. When they return to Paris in the fall, Picasso begins experimenting with the papier collés invented by Braque that summer. With this technique they glued papers printed or painted in their compositions. With this they initiate a new phase of the cubism in September of 1912.

The pieces of paper allude to a particular object, they are cut with a relevant shape or include graphic elements that clarify the association60. With this they will work:

(...) papers of various forms and descriptions: wallpaper, newsprint, bottle labels, musical scores, even fragments of old books discarded by the artist. Covering themselves like the papers of a desk or a work table, these leaves are aligned with the frontality of the surface that sustains them; And further, by pointing to the frontal condition of the surface, they also declare that, as paper, it is thin, as deep as the distance between the topsheet and those beneath it.61.

Regarding the purpose of the papier collés Picasso will declare that they sought to challenge reality in nature:

We tried to get rid of trompe-l'oeil to find a trompe-l'oeil. We didn't any longer want to fool eye: we wanted to fool the mind. ... Newspaper was never used in order to make a newspaper. It was used to become a bottle or something like that. ... If a piece of newspaper can become a bottle, that gives us something to think about. ... This displaced object has entered a universe for which it was not made and where it retains, in a measure, its strangeness. And this strangeness was what we wanted to make people think about because we were quite aware that our world was becoming very strange and not exactly reassuring62.

The transition from analytic cubism to synthetic cubism represented a fundamental moment of artistic evolution. The last years of the pre-war, from 1912 to 1914, were the era of development of the cubist collage, Picasso and Braque change substantially the relationship with form. The introduction of colored surfaces and the fact that shapes became more pronounced opened a new path.

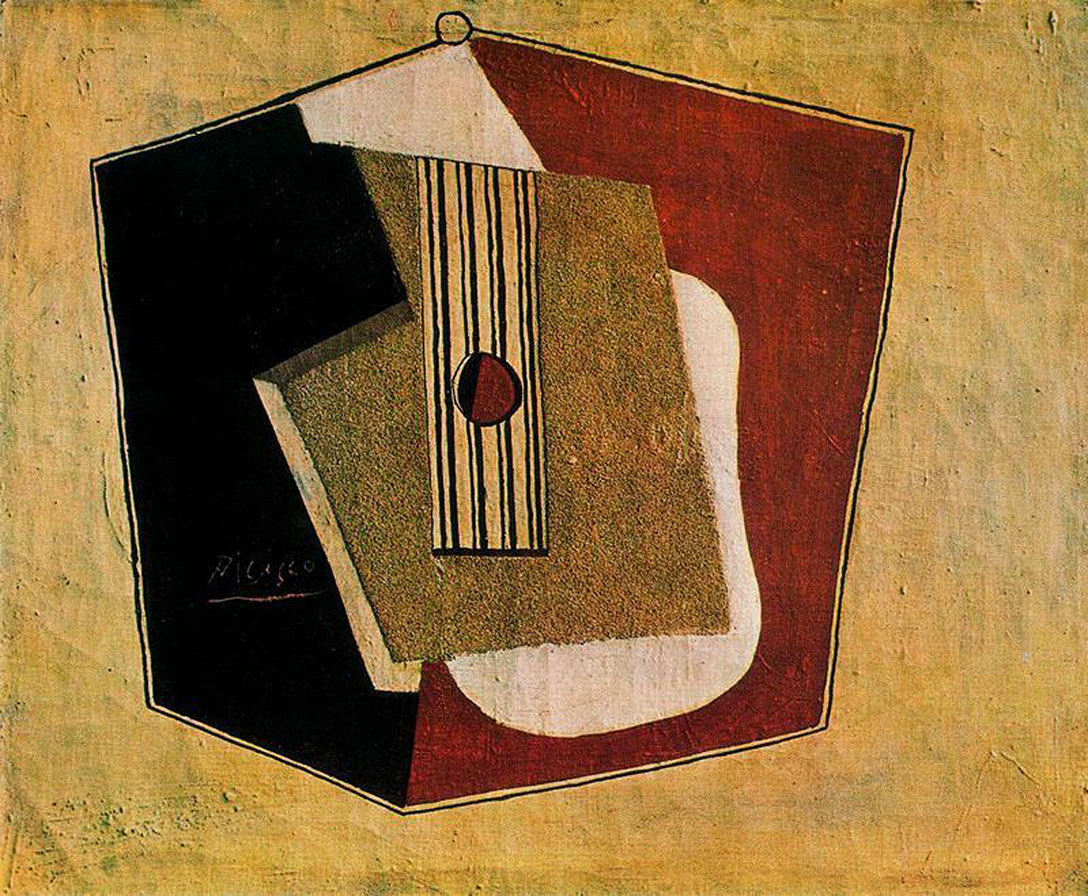

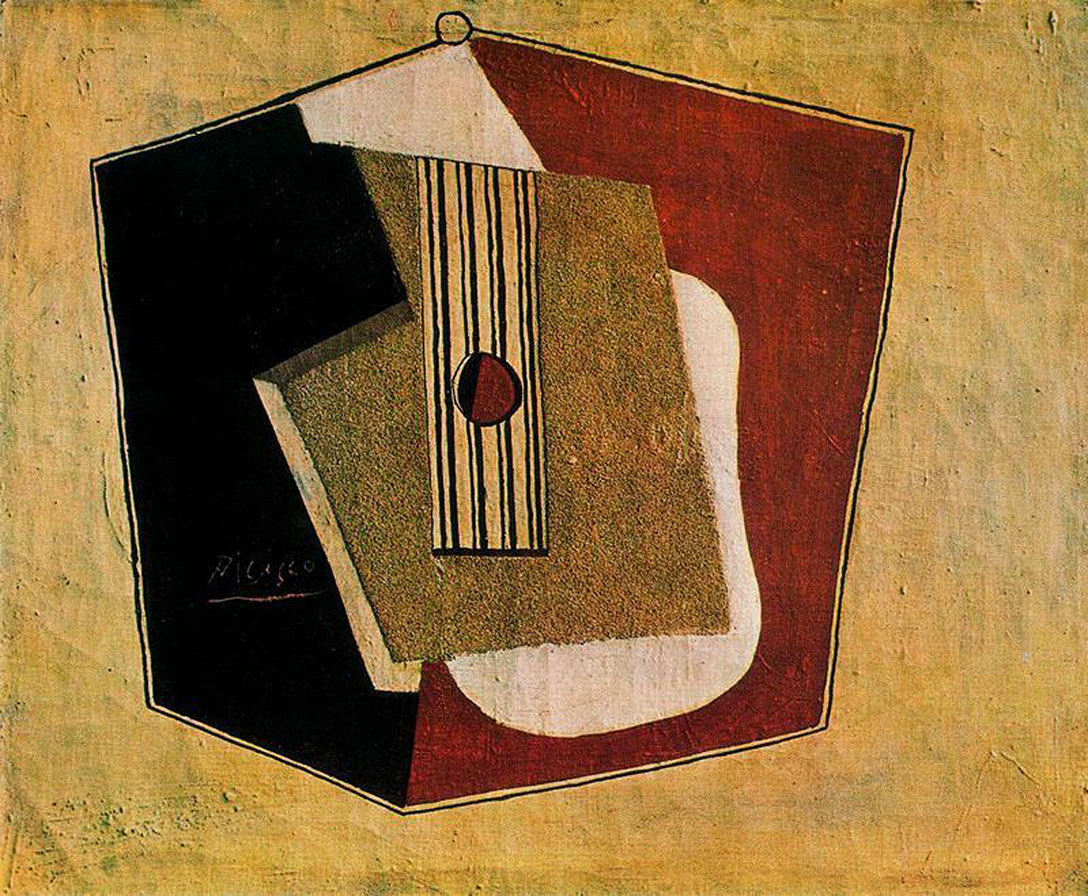

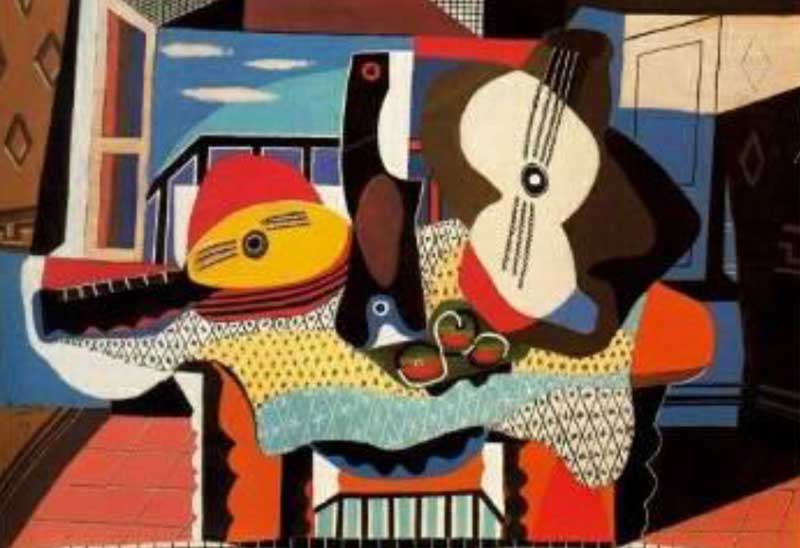

The presence of musical instruments is numerous and significant in all phases of cubism. Braque, music lover and interpreter of the accordion, was the link between Picasso and cultured music. Braque also played the concertina, flute and violin. This last instrument is part of his works from analytic cubism63. Picasso's painting shows the presence of musical scores, musical instruments (especially violins) and musical interpreters64.

|

|

|

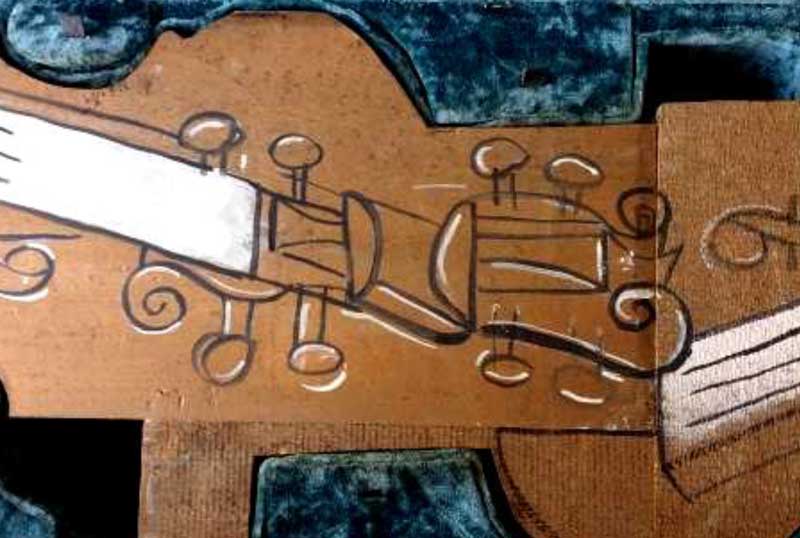

Image 6.4. Violin at the cafe (1913) |

Image 6.5. Violin hanging on a wall (1913) |

|

|

|

Image 6.6. The Guitar (1913) |

Image 6.7. Guitars, partitures and glass of wine (1912) |

|

|

|

Image 6.8. Violin (1912) |

Image 6.9. Violín and fruits (1912) |

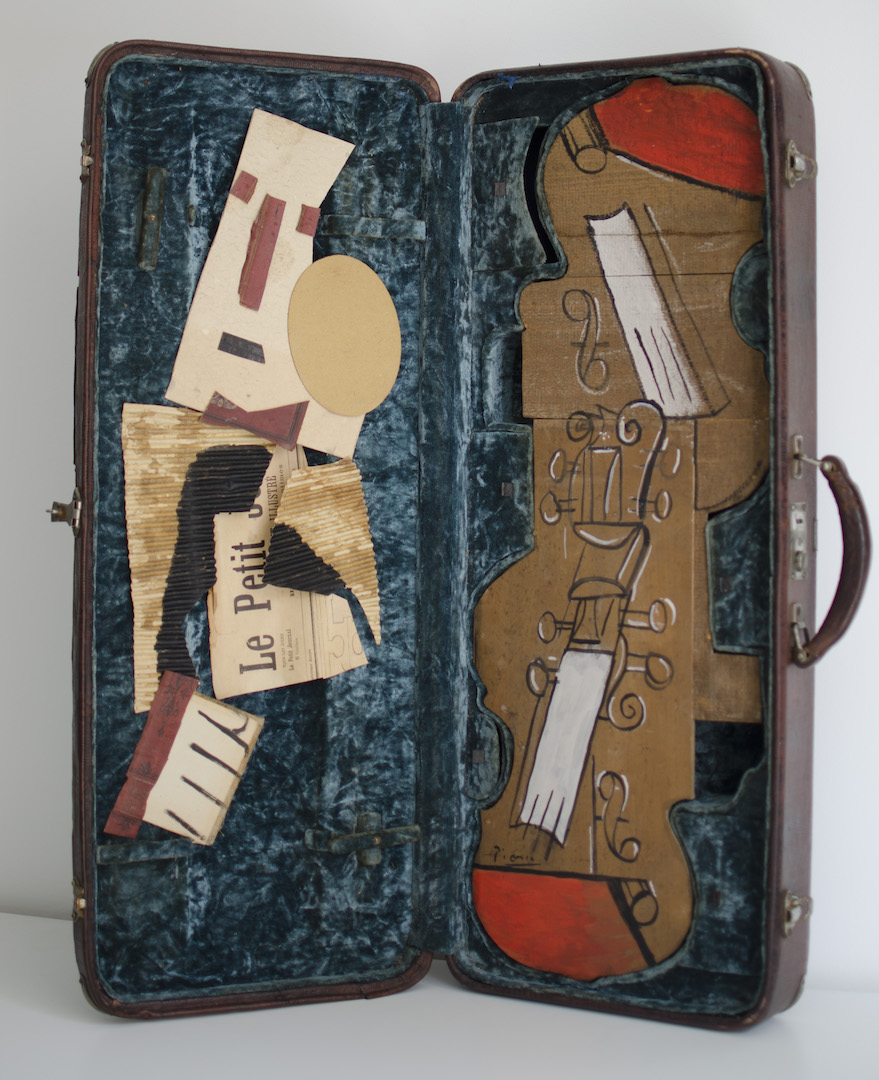

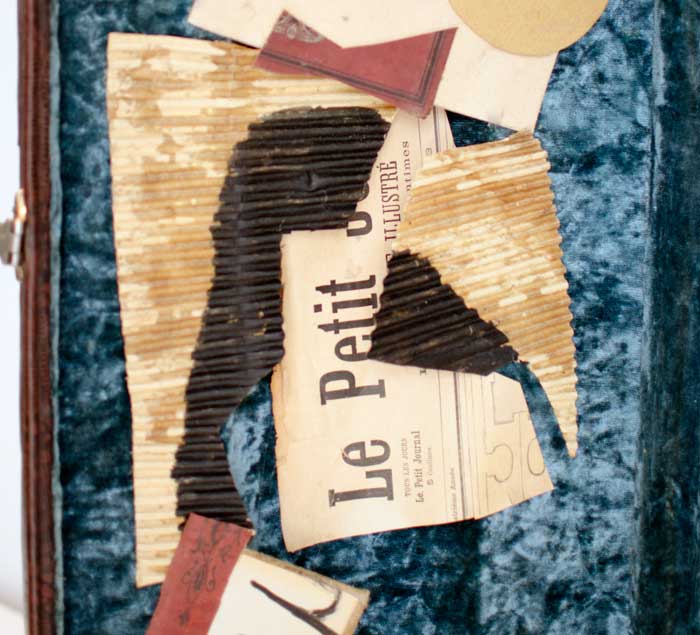

Image 6.10. Synthetic collage, inside of the case

|

| Image 6.11. left side of the collage |

The present piece is realized in a case for two violins, whose dimensions are 80 cm. long, 32 cm. wide and 11 cm. of depth with the closed case. With open case measures 80 cm. long, 64 cm. wide and 5.5 cm. of depth, approximately.

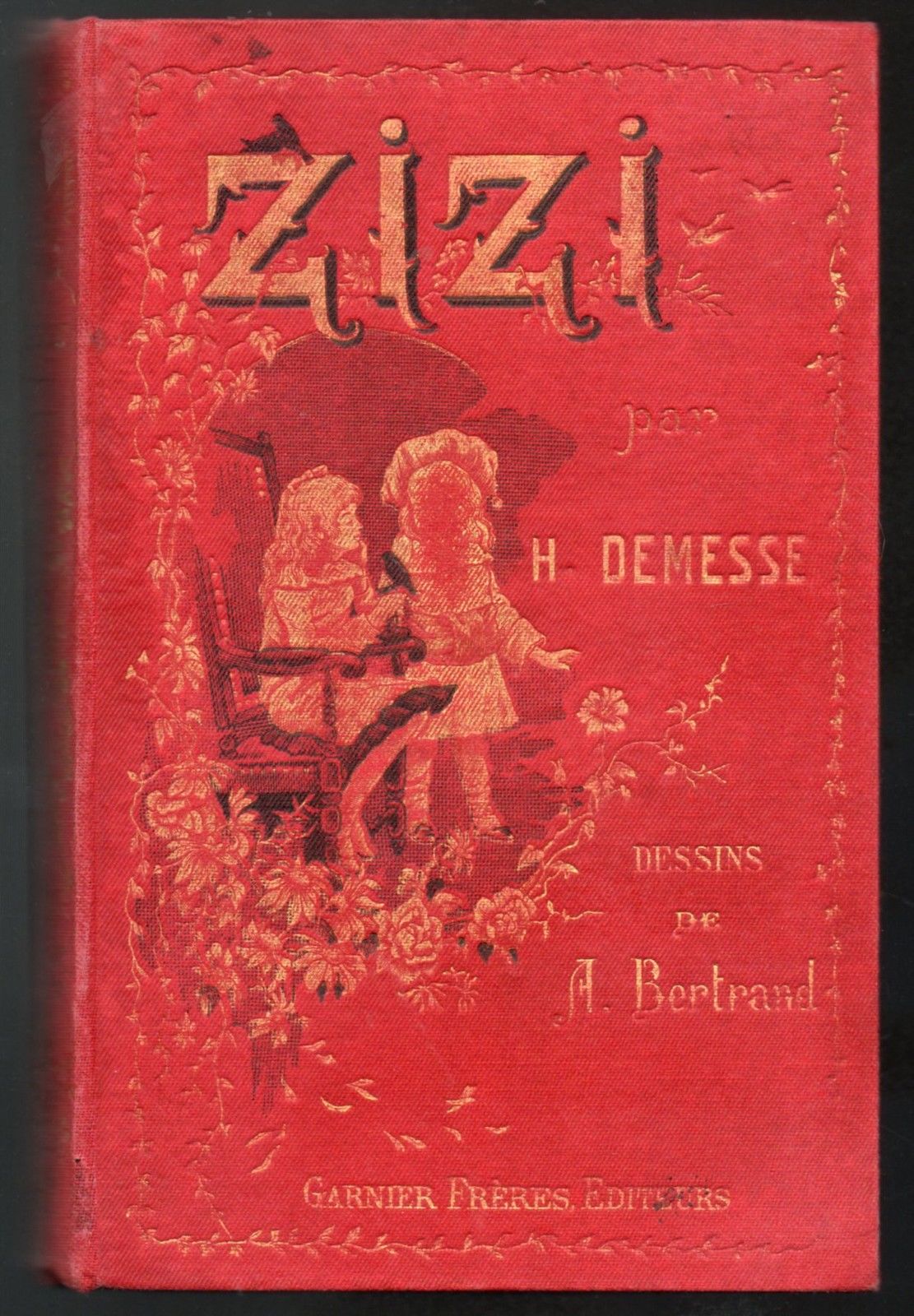

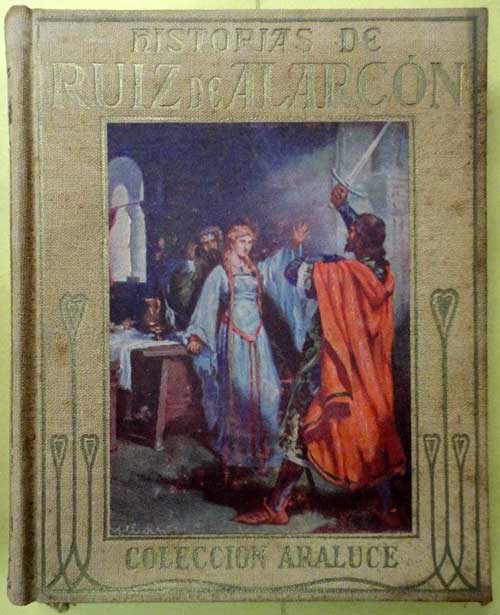

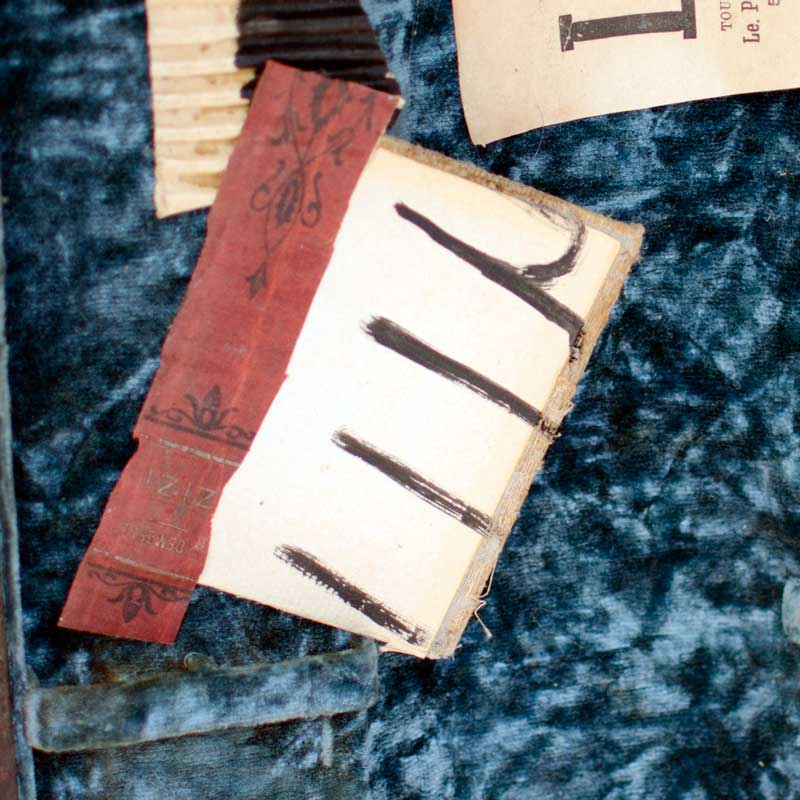

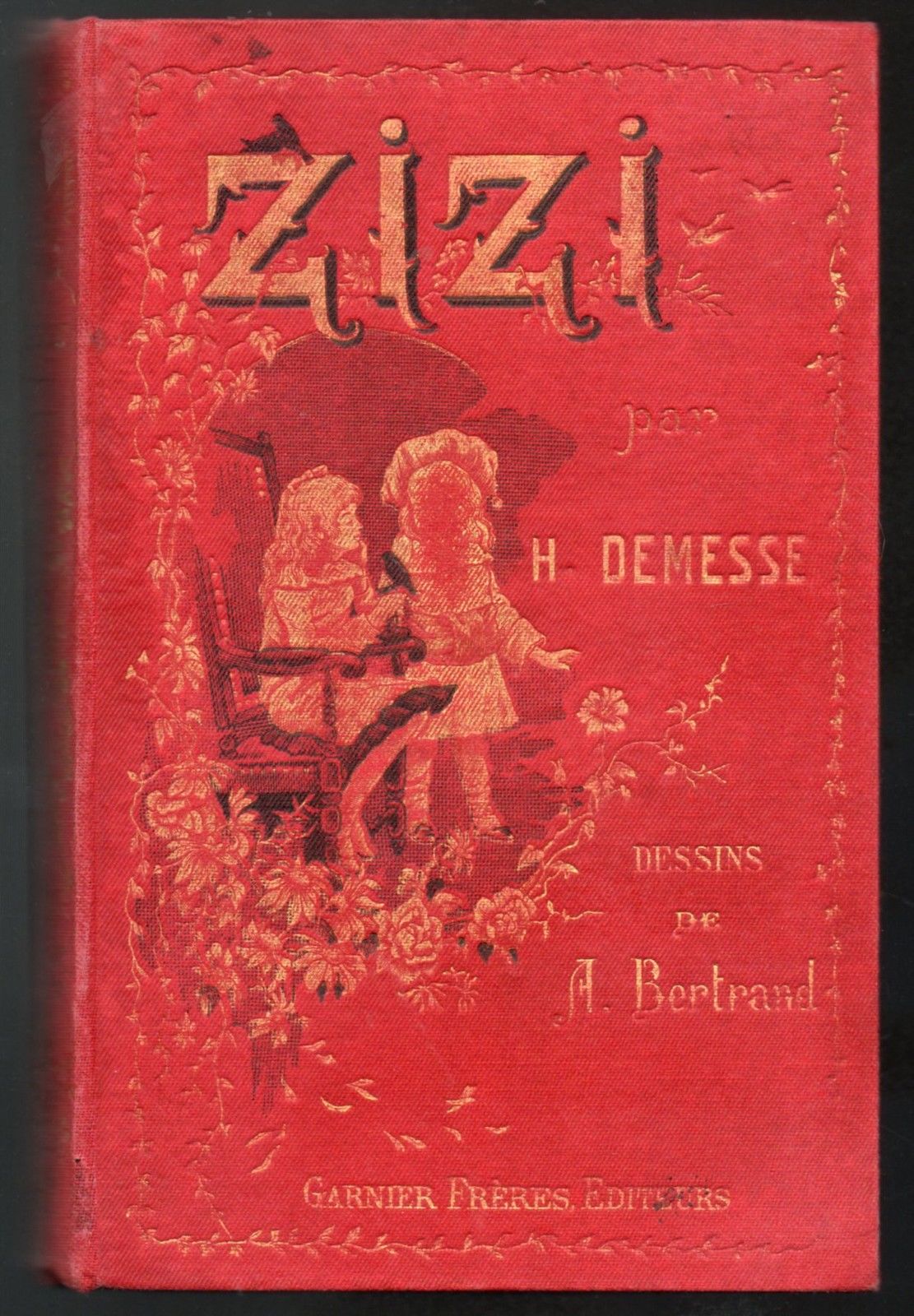

The left side corresponds to a section of the collage that is composed mainly of a human figure, presumably of a violinist. The face is made on the basis of a cardboard cutout of light ocher color. Below are two pieces of the same type of corrugated cardboard, a fragment of the newspaper Le Petit Journal and a fraction of the cover of the book Historias de Ruiz Alarcón, placed in inverted position and of reverse, fulfilling the role of hand with fingers, which arise on the subject of graphical interventions with black ink. Different applications of the face of the violinist, such as the bow and his right fist, are made with cuts from the cover of the book Zizi. Historia de un gorrión de París by Henry Demesse. Other cuts are an ocher color oval (cut industrially) and a black fragment that corresponds to the mouth of the figure.

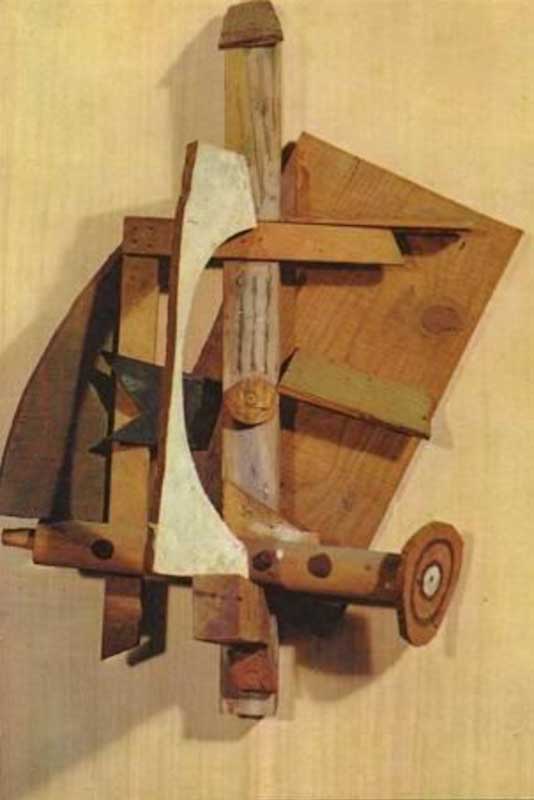

The right side has a composition composed of two violins that meet in reverse. They are made of fragments of two types of wood, mounted on wooden supports that give it the necessary height to be flush with respect to the upper surface of the hollow of the case. The obverse of the wood with the shape of violins, is intervened graphically with the technique known as gouache.

|

|

|

Image 6.12. Back side of the violins. There are different woods assembled and the supports that give height to the composition |

Image 6.13. Right side of the collage. There are different woods assembled and the supports that give height to the composition |

With the first review, it has been possible to carefully analyze the distribution of materials, brushstrokes and graphics of the piece attributed to the artist. The palette and materiality used in the work, are relevant data to understand the attribution to the artist's hand.

In relation to the palette, the use of three visible colors is seen in the collage: red, white and black. All three, by optical inspection, exhibit a covering behavior compatible with technique gouache. This technique corresponds to a watercolor of thin layers of paint, which produces the effect of being thicker than it is in rigor. Its finish is opaque, matte and uniform65, which is corroborated with what is observed in the experimental work and with the technique commonly used by Picasso in several of his works66.

Below are two details of picassian works that present technical similarity of gouache with the studied piece.

|

|

|

Image 6.14. Detail of the three colors used in collage |

Image 6.15. Detail with flush focus of the colors black and white |

|

|

|

Image 6.16. Detail of Guitare et bouteille de Bass (1913) |

Image 6.17. Detail of The clarinet and violin (1913) |

According to the vibration analysis by Raman microscopy and attenuated total reflectance (ATR) FTIR spectroscopy, developed by Tomás Aguayo for Veritart67, it was obtained that the spectrum of the white sample shows the signals of titanium dioxide, in the form of rutile.

According to the research of Millán del Pozo, about the use of titanium dioxide in Europe, the following is extracted:

(...) titanium dioxide as pigment, has been used scarcely since 1870 to 1895 and in 1895 was sold in titanium dioxide preparations in Germany, France, UK and Italy, increasing its progressive use as a pigment, which with all probability caused its commercialization (...) Max Doerner in 1890 confirms the satisfactory use of the titanium in its mixture with the lithopone, this in itself evidences its use68.

In the form of rutile, the titanium dioxide would have begun to take place around the year 1945, due to its technical-pictorial properties superior to the anatase, another form of crystallization of the titanium dioxide that would have been produced exclusively until the year 193869, however, this explanation of the synthesis and use of titanium dioxide is controversial, since there is evidence of rutile and anatase in pigments of pre-Columbian70 ceramics, which implies that these forms of crystallization of titanium dioxide occur naturally, without that the pigment must necessarily be synthesized in a laboratory. This evidence overthrows the possibility of using rutile, anatase or titanium dioxide as an element that chronologically guides an artistic or archaeological piece.

Given the above, titanium dioxide in the form of rutile, is not a pigment that provides information on the date of an artistic or archaeological piece.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, titanium dioxide, for its covering properties, is suggested use for the gouache technique71; this condition that makes it compatible with the technique used by Picasso.

In reference to the red pigment of the collage, the vibration studies by Raman microscopy yielded compounds compatible with those used in the "anilines". In fact, the sample presents the characteristic profile of a type of synthetic pigment called diazopirazolone. This type of pigments belong to the sub-group of the diazo pigments and are compatible with the anilines, which thanks to their great dyeing power are used in smaller quantities to obtain a hiding power, a condition that enables them to be used as artistic material.

Image 6.18. Detail of the red pigment in the technique gouache of the studied piece

Considering that this designation (gouache) covers a wide range of technical and material possibilities, where the anilines are included, we find it especially significant that it coincides with the modus operandi of the artist, as many of his works refer to72.

The work shows black brushstrokes that according to the same Raman technique applied to Veritart, correspond to the carbon pigment, which also as a dye composes several of the works of the author73.

Image 6.19. Detail of the black brushstrokes in gouache technique of the studied piece

|

|

|

Image 6.20. Clarinet and violin (1913). Brushstrokes with gouache technique |

Image 6.21. Still life with violin and fruit (1912). Use of coal in collage sections |

Likewise, an approach that dissects its material components, collect by its formal associations and materials used by Picasso in times of synthetic cubism, the strong influence of Braque and figures easily linked to the characters of the Parade ballet, as well as gathering objects of Tradition (Historias de Ruiz de Alarcón 1914 and violin case made in Barcelona), French tradition (Zizi, Historia de un gorrión de París (1892/1910/1912?) and Le Petit Journal (1893). All materials dated until 1914.

The piece analyzed offer a volume of information that, far from having a merely subsidiary character, provide important clues to solve the unknowns of style, dating and brought us to very frequent details within the processes of creation of the artist.

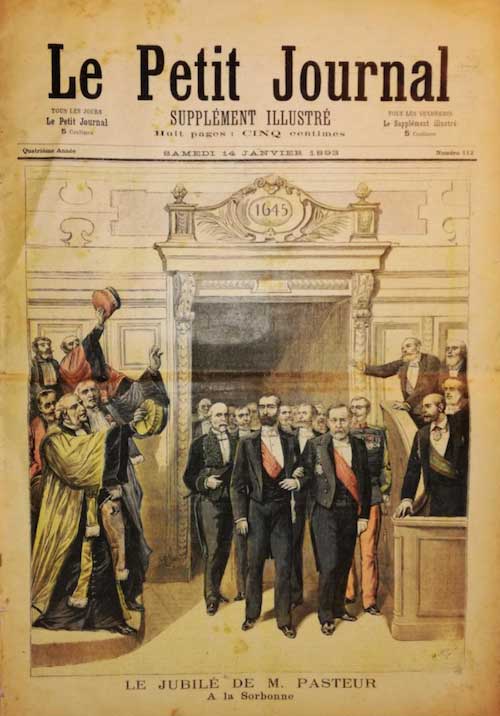

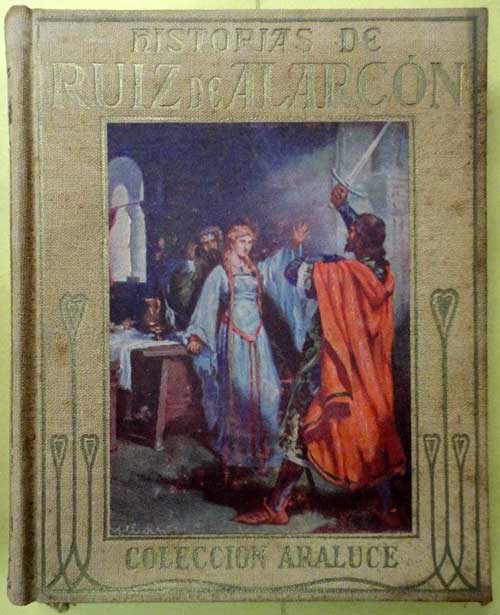

The study shows that, for this work, Picasso reused parts of two books and a sheet of Le Petit Journal (corresponding to the cover). These materials were subjected to documentary examinations in the laboratory of Veritart and by virtue of the results, it is possible to indicate that the materials are of data no more than the year 1914. The cover of the book Zizi, can be the case of a special edition of the year 1892 or a second or third edition of the years 1910 and / or 1912 respectively. In reference to the book Historias de Ruiz de Alarcón, the studies show that the section used in the work is of the first edition of the year 1914 and the cover of the newspaper Le Petit Journal, corresponds effectively to the drawing of Saturday 14 of January of 1893. This shows that part of the material constituting the work presents a chronology equal to or less than the year 1914.

|

| Image 6.22. Detail of the violinist head |

Inside the suitcase you can see the representation of a musician in the act of performing a violin. The technique is clearly papier-collé with few graphic or pictorial interventions. The head is made of cardboard of light ocher color, cut, following a rectangular / geometric profile. The right profile is pronounced at a slight angle, suggesting the posture tilted towards the shoulder, has two crevices made intentionally in the brow and on one side of the bow tie, which reinforce the movement of the face towards the violin.

The cut of oval paper, of ocher color, contributes through a game of forms,

the effect that synthesizes the action of the musician in the act of playing.

The eyes, nose, tie and cuff of the sleeve are cuts in burgundy color of the book Zizi. Historias de un gorrión de París by Henry Demesse, published as a special edition of 1892 or, in case, would be a second or third edition of the 1910s or 1912s.

Image 6.23. Cutouts of the book Zizi on face (left figure), bowtie (upper right figure), fist (lower right figure)

Image 6.24. Zizi (¿1892/1910/1912?)

The hand corresponds to a fraction of the book Historias de Ruiz de Alarcón, same that has been used by the reverse and in inverted position.

Image 6.25. Fraction of the cover of the book Historias de Ruiz de Alarcón. It is observed by means of a mirror, the evidence of the cover

Image 6.26. Historias de Ruiz de Alarcón (1914)

The mouth is a patch of black color. All the cuts of this book follow straight forms, contrasting with the oval to the right side of the face. This description is in agreement with the simple geometric figures, which are typical of the period of synthetic cubism; This is so, that the denomination of synthetic implies a synthesis and simplification of the geometric compositions, with the purpose of approaching the spectator74. In this sense the geometrical lines of the composition of this work are entirely compatible with the purpose of this period of cubism.

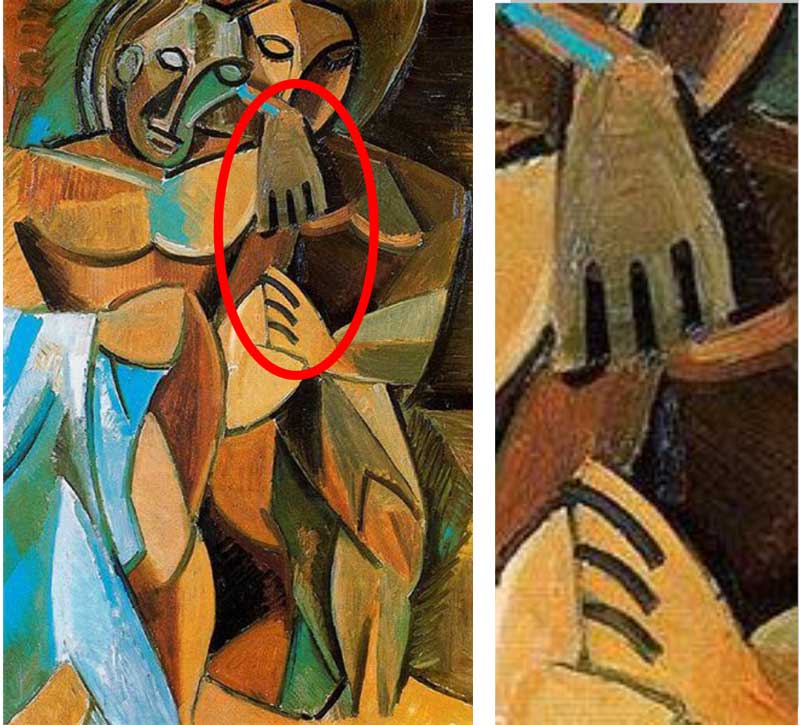

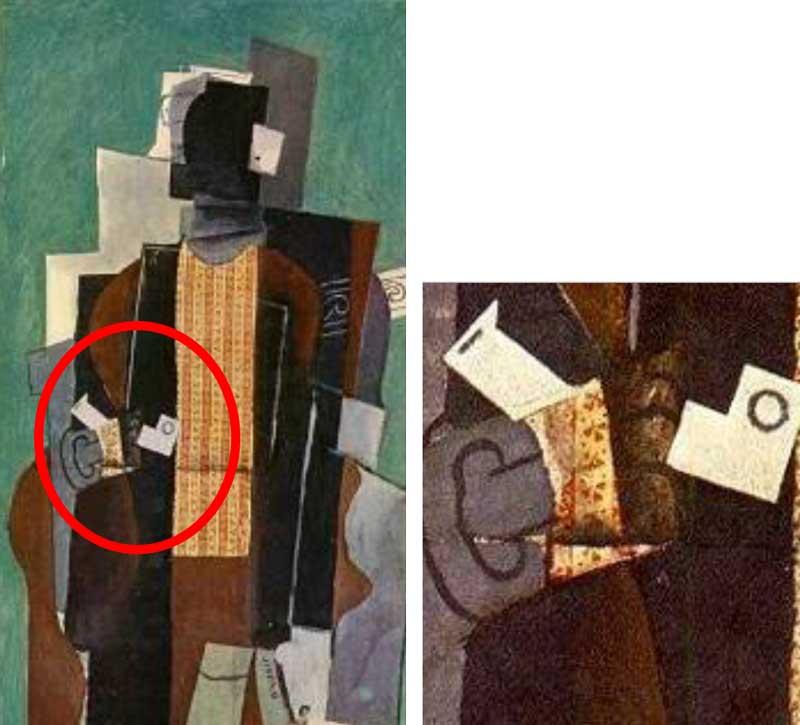

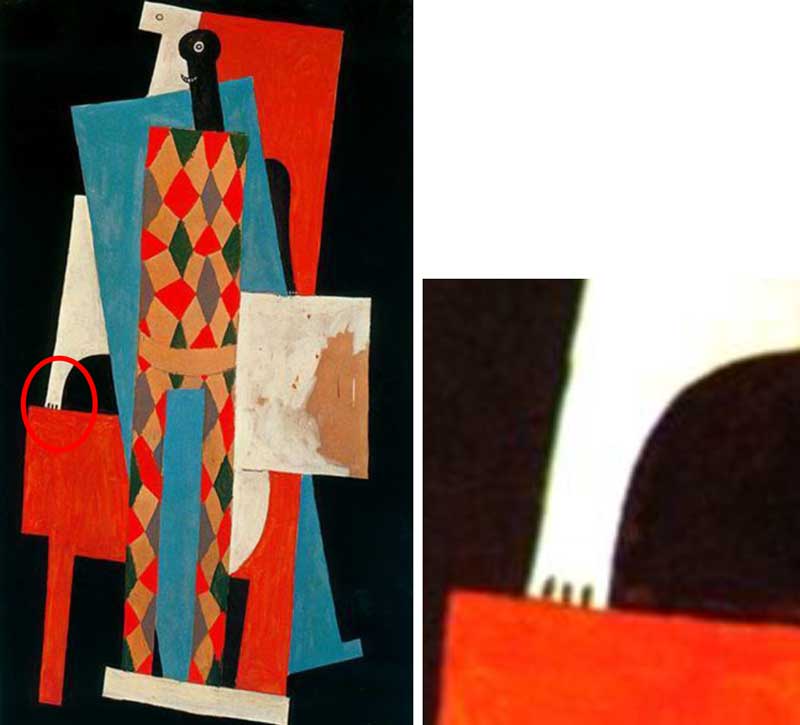

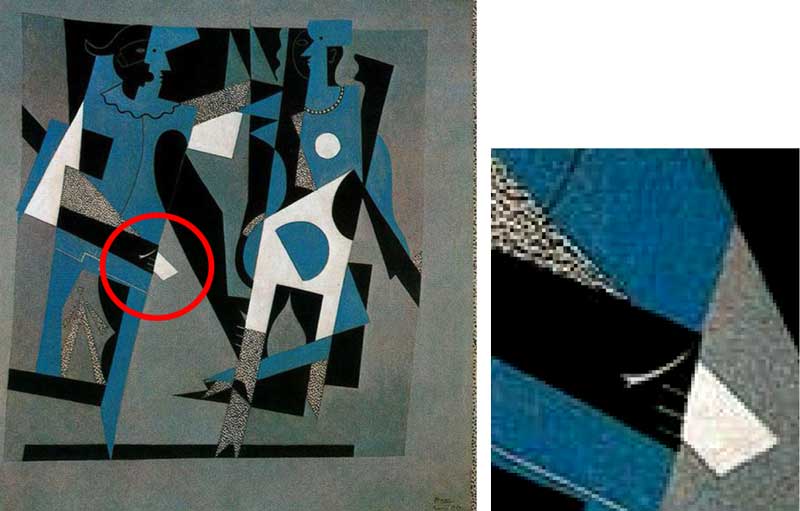

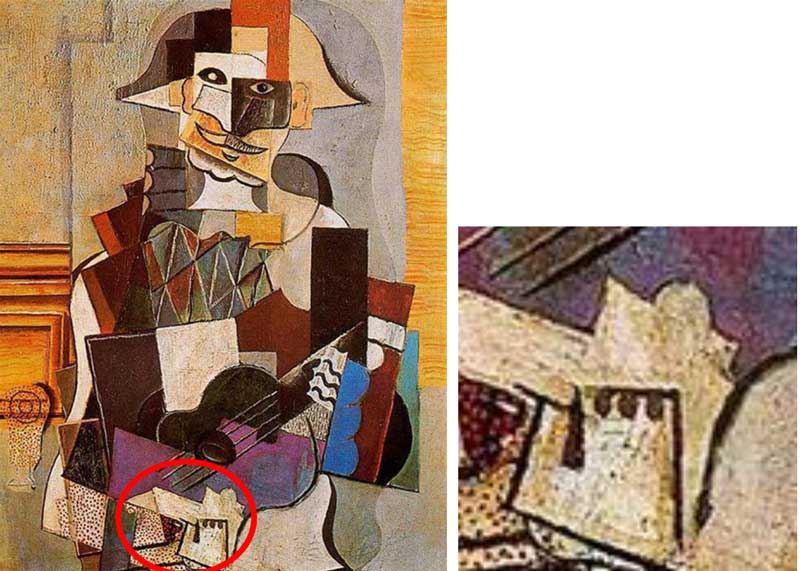

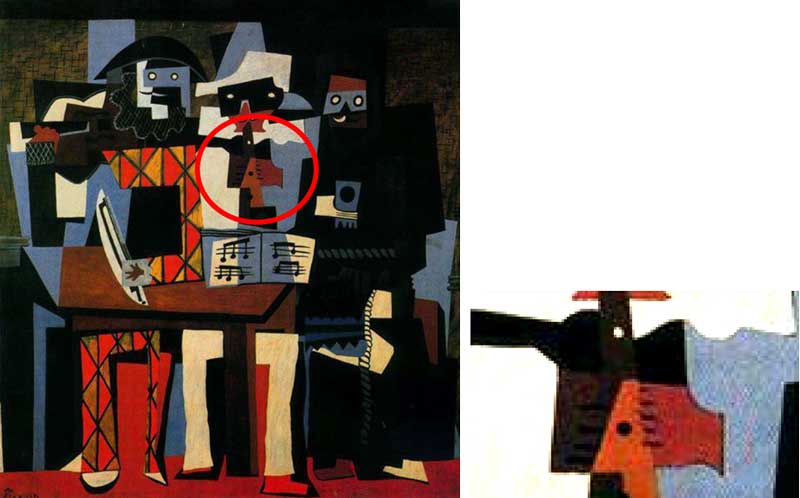

In the images that follow, it is possible to recognize in the characters - whether musicians, saltimbanquis, a head or a woman - physiognomies related to the musician's face in the work subject to analysis, due to the geometric simplicity of its forms.

Image 6.27. Head of a man (1913)

|

|

|

Image 6.28. Harlequin (1915) |

Image 6.29. Italian woman (1917) |

|

|

|

Image 6.30. Harlequin with violin (1918 |

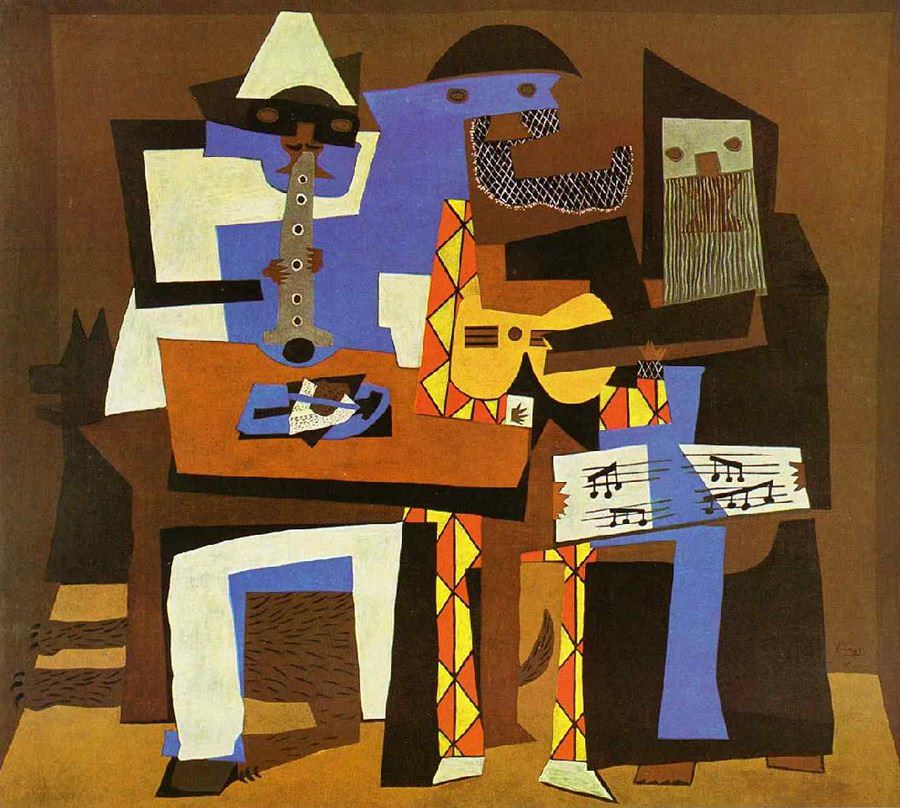

Image 6.31. The three musicians (1921) |

The complete figure of the left wing of the work analyzed, follows a zigzagging direction, creating a dynamic movement that dialogues with the lines presented by the right side of the work.

As indicated above, the style of this work belongs to synthetic cubism, marked by a richer color range than that of its previous stage (analytic cubism). Through a material multiplicity, the artist reconstructs the shape with different volume and textures. For this, select a bounded number of planes to recognize better the subject being represented. In this artistic stage, the invention of the analysis of forms, along with an enrichment of color and a greater importance given to textures75, begins to predominate, which is in line with the use of the red color of this work that gives strength, character and vivacity to the studied work, together with the multiplicity of elements that nuance the different parts of the work with textures, a condition that dialogues with the technique of collage, in which Picasso included pieces of newspapers, magazines, canvases, cutouts; materials that had the main purpose of defining the spatial organization by itself, which managed to order the structure from vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines. Consequently, the expertised work, fully complies with this explanation.

As in this work, the presence of musical instruments can be observed in various creations of Picasso, especially those of strings that are usually more identifiable in creations that present a rupture of the homogeneous forms and the continuity of the contours76. In the works of this period, Picasso fuses human figure with instrument, musical score with palette of painter, object with subject.

Regarding the body of the musician present in the studied work, the style and lines, geometric cuts and the predominance of black, white and red / burgundy; as well as the composition of forms, can be recognized in Picasso's work for the Parade ballet in 191777. In picture 6.32 it is possible to appreciate both a scene and part of the costumes of the ballet Parade.

Image 6.32. Parade (1917), scenes and costume.

Regarding his work oriented towards three-dimensionality, Picasso states in 1914:

These paintings will suffice to cut them - since, in short, the colors are but indicators of different perspectives, planes inclined on one side and another - and then couple them according to the indications given by the color to be in the presence of a "Sculpture"78.

Image 6.33. Torso of the violinist of the collage

The jacket of the analyzed piece is made of corrugated cardboard (packaging material). It is also painting black on the inner margins and on the sides, which gives him the light-dark contrast that is perceived as a different plane, giving it a deep effect. Regarding the presence of corrugated cardboard in the work, it is interesting to pay attention to the use of different cartons in the cubist works of the artist, characteristic of the experiments of these years in Picasso as well as in Braque and in the futurist movement79.

The fragmentation of form and then the recomposition of loose fragments contribute to exalt its visual and tactile qualities. The suit's shirt is made with a cut from the newspaper Le Petit Journal, dated January 14, 1893, where the phrase Le Petit is mainly visible.

The only element drawn is the hand, which appears as a black sign, on a piece of white cardboard, from the book Historias de Ruiz Alarcón of Araluce Editorial, Barcelona, Spain, dated 1914; visible information only when looking at the back side of the fragment (action performed with a mirror). Looking at the figure of the musician in totality, the hand is an element that draws attention by its solidity and by its simple and synthesized confection of traces in its great majority, straight ones; which is corroborated by similar examples in form and style in many of Picasso's works80.

Image 6.34. Detail of the hand of the studied collage

Image 6. Left: Friendship (1908). Right: Detail of the hands

Image 6.36. Man with pipe (1914). Right: Right hand detail

Image 6.37. Left: Harlequin (1915). Right: right hand detail

Image 6.38. Left: Harlequin and woman with necklace (1917). Right: detail of the harlequin's right hand

Image 6.39. Left: Harlequin (1918) Right: Harlequin's right hand detail

Image 6.40. Left: Musicians with masks (1918). Right: detail of the hands of the 2nd musician

|

| Image 6.41. The guitar (1916) |

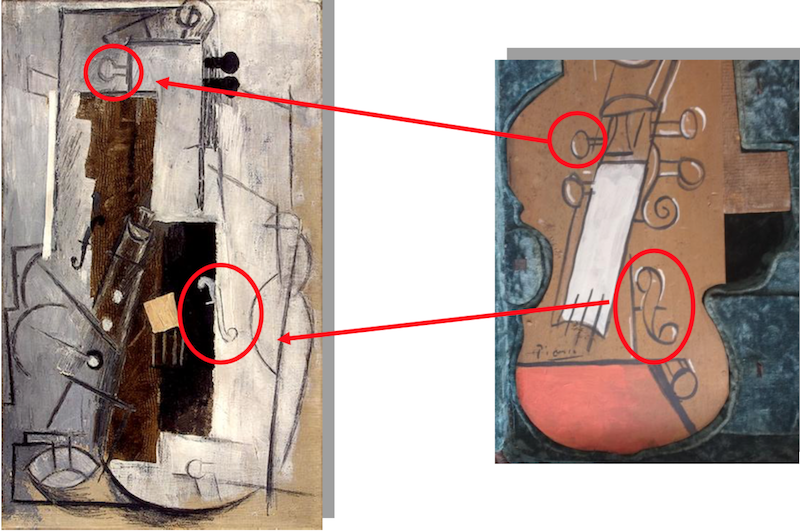

From a set of fragments of wood is recognizable the design of two violins. The representation occupies the whole surface of wood. The technique used with the paint materials is gouache and the colors presented are white, black and red. On this side the graphic line recreates the shapes with colored planes. White and black are also, respectively, light and shadow; The red note, defines the extreme portion of the top and bottom of the complete silhouette. This color is present in several works that refer to stringed instruments. Likewise, the interior of the case that has a blue velvet lining, also contributes a tone that in the picassian works has been common in the period of the synthetic cubism. The following images prove it.

|

Image 6.42. Violin hanging in the wall (1913)

Image 6.43. The guitar (1916)

Image 6.44. Guitar and score (1920)

Image 6.45. Mandolin with guitar (1924)

In the work in question, according to a requirement of symmetrical balance, the graphic weight is "balanced" through the blank sections corresponding to the fretboard (sector where the instrument strings are located on the handle) of the violins and limbs in red. The wood surface was left with the natural color: so that the material represents itself, characteristic aspect of the synthetic cubism.

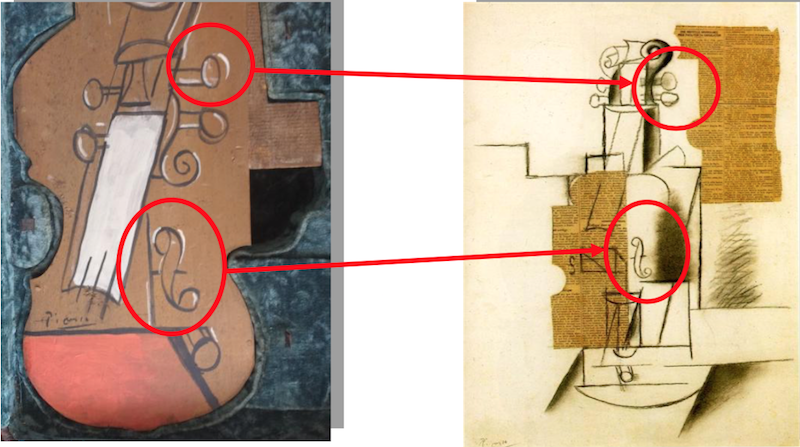

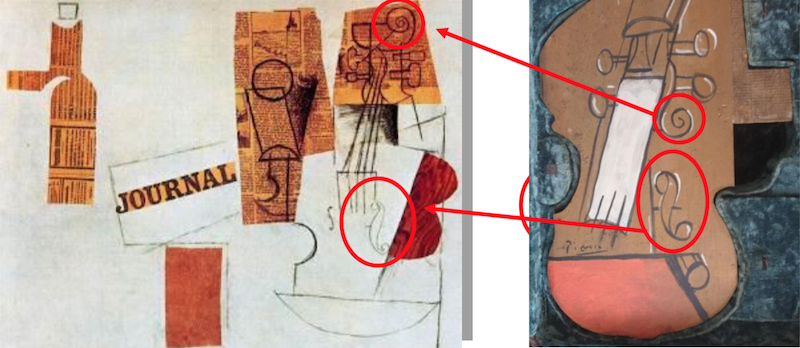

It is perceived a synthetic image that presents simple elements that arrive at a harmony in spite of the rustic materials used. The representation is posed as a game of optical illusion, where the graphic boundary between the first and second violin is lost, in a dynamic and sinuous composition. The white portions of the tuning forks, rigid and rectilinear, contrast with the movement of the curves of the composition. These elements make a counterbalance to the figure on the right in coherence with the structure of zigzag breaks, according to a visual balance of the complete work. One can confirm the need to understand these oppositions between curved and straight lines, such as visual inquiry, in relation to the examples given below. At the same time, it is relevant to observe the volutes and the "F-holes" as stylistic elements, which are repeated in other works of Picasso.

Image 6.46. Left: detail of the studied collage. Right: Violin (1912)

Image 6.47. Left: Bottle, glass, violin (1912). Right: detail of the studied collage

Image 6.48. Left: Clarinet and violin (1913). Right: detail of the studied collage

Looking back at Picasso's vast work, it is significant that between 1912 and 1915 the artist creates a series of paper, cardboard, wood and tin constructions with painting interventions that transfer the discourse of the collage from the two-dimensional plane to a three-dimensional plane, arriving at works mixed between sculpture and painting.

|

|

|

Image 6.49. Violin (1913) |

Image 6.50. Mandolin (1913) |

|

|

|

Image 6.49. Violin (1913) |

Image 6.50. Mandolin (1913) |

The images 6.49, 6.50, 6.51 and 6.52 show the picassian collages and / or sculptures of synthetic cubism, which, by style, composition, structure, stylistic seal, are compatible with the analyzed collage, even more so when white gouache has frequently participated as a technique.

For Ingo Walther, the papier collé led Picasso to think again about the sculpture - previously he made some from 190281 -. The bonding of paper on the surface would have been a step forward to overcome the two-dimensional character of the painting. When adding other materials the paintings were acquiring more and more relief.

The development towards the three-dimensionality as well as the rupture of the structures happened in several stages until completely independent objects, is the case of Violin and Bottle on a Table of 1915/16, a construction that consists of pieces colorfully painted of wood, nails, and strings. With this new idea, Picasso started many revolutionary innovations in twentieth-century sculpture. The traditional method had been additive or subtractive to the present (...) Now, however, it is a matter of using simple ready-made components and to fit them together into varied and complex structures. This was, in effect, the beginning of a new chapter in the history of sculpture, a chapter that can be called "constructivism"82.

It is relevant to note the literary elements present in the work, since there has been much speculation about the possible intentions of Picasso incorporating these intertextualities, even though they are not always recognizable to the viewer. For Tinterow and Stein the cuts in his work refer to various issues, from the Balkan war and the conflicts in the French mines, to critical government issues. Which has led them to suggest that Picasso purposely selected certain texts83.

An example of this intentional selection of written information is found in the study developed on the Suze ́s bottle (1912)84, which presents texts that confer a political and social dimension to the image. Picasso juxtaposes journalistic articles referring to the terrible events of the First War of the Balkans with stories of Parisian frivolity. Along with the texts, the fragmented forms, deformed in this cubist image, allude to the conditions of modernity as the lack of coherent perspectives or meanings in a world in constant change, which makes it clear that Picasso's work , can be seen as a paradox that on the one hand warns against the absurdity of modern life and on the other, invites the delight of the simple pleasures of life.

Image 6.53. Suze’s bottle (1912)

Consequently, it is possible to infer that the presence of newspaper clippings and fragments of books, assign to the work object of analysis, greater information that is seen with the naked eye, a type of implicit information that is then tried to elucidate:

Le Petit Journal: The present page in the work corresponds to the cover that illustrates the jubilee of Luis Pasteur in 1892. In this activity Pasteur affirmed:

Do not be tempted by the denigrating and sterile skepticism, do not let yourself be discouraged by the sadness of certain hours that weigh on the Nation. Live in the serene peace of laboratories and libraries. Ask at the beginning what I have done for my instruction? And as you advance in life, what have I done for my country? Until you have the immense joy of thinking that you have contributed something to the progress and good of humanity ... But whether your efforts are more or less favored by life, what matters is, when one approaches the great goal, have the right to say: I have done everything I could85.

Although one cannot be certain of the political intentionality of the cut used, there are arguments to think that the warlike environment facing Europe at the time when synthetic cubism developed could have induced Picasso to express artistically a political and / or morality regarding the consequences of the war and the scope and implications of individual responsibility in the social sphere, which is quite compatible with the thesis of some researchers who claim that Picasso implicitly connoted relevant information, such as a call for attention, contrast or simple reflection86.

Now, why would Picasso have selected a fragment of Le Petit Journal? According to Harrison, Frascina and Perris - in the context of the analysis of picassian cubist works - indicate that the media, including the written media, such as Le Petit Journal, are forms of social organization that have implicit values and beliefs that mobilize people87, therefore, for Picasso, a fragment of this newspaper, would not only fulfill a role constituting a collage, but would contain a deep symbolism where certain values and social beliefs would be present.

Image 6.54. Le Petit Journal (1893). indubitable Document

Historias de Ruiz de Alarcón (1914 edition): This Spanish book compiles three stories by Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, writer of the Spanish Golden Age, who develops a moralist literature. The narratives correspond to El tejedor de Segovia, which deals with the need for good government; Las paredes oyen, whose argument refers to unrequited love and the triumph of pure love over gallantry; and La verdad sospechosa, which deals with a liar.

Juan Ruiz de Alarcón is considered an influential baroque Spanish playwright who has versed his work in themes related to morality, emphasizing the idea that the world is a hostile and deceptive space, where appearances prevail against virtue and truth, attacking the customs and social vices of the time88.

It is interesting to note that what is related to Ruiz de Alarcón is linked to morality, especially if the thesis that Picasso used the written media with an underlying ideological desire is considered correct, a context in which, morality would be a theme usually posed in Its artistic manifestations. This morality would, of course, be influenced by Marx and Engels, ideologists who proposed that ideas, values, and beliefs about society would be mere assumptions89. These assumptions would be under the guideline or guardianship of a few subjects who have the power to define what is shown or what is made to believe others, who would be responsible for impregnating a supposed sense of reality in society. This small approximation to the ideology of Marx and Engels, which significantly clarifies that of Picasso, is insinuating when we return to the premise of Ruiz de Alarcon that indicates that the world is a hostile and deceptive space, where appearances face the virtue and the truth. It is also insinuating when it is observed that in the collage, the fragment of the book Historias de Ruiz de Alarcón is inverted, can only be observed with a mirror, that is to say, the viewer only sees a hand with a white background, does not know that it is a cover that is, "reality" is not available to be captured by anyone, only by a few who have the ingenuity to suppose the existence of valid information in places and in Unconventional forms.

Image 6.55. Stories of Ruiz de Alarcón (1914)

Zizi, historia de un gorrión de París: this French book corresponds to a children's story written by Henry Demesse, dealing with the adventures of a small sparrow narrated in the first person.

It is important to note that the cuts that are used in the collage investigated, allow to recognize the book from the name "Zizi", which if read alongside the text of the newspaper "Le petit", the possibility of conforming the phrase "Le petit Zizi ", that translated corresponds to "small sparrow ". This relation of concepts, is even more interesting if Braque is considered in 1913 the work Petit Oiseau90, whose translation would be "little bird". In this work Braque evidences the title of the work by incorporating the text into a score, as suggested by Le petit Zizi.

As already mentioned, the influence of Braque in Picasso and vice versa was recurrent, so it is suggestive the possibility of an intention of dialogue between these two works.

Image 6.56. Zizi (¿1892/1910/1912?)

Imagen 6.57. Petit Oiseau (1913)

The work analyzed is intrinsically a collage: it uses the objet-trouvé, the case of two violins, which becomes the matrix of the work, which seems to be a playful proposal where the viewer discovers the object-work, a collage inside, like the surprise when opening a box of spring with a clown or saltimbanqui to the interior.

It is made from a case for two violins, which allows you to open it and find the elements of the collage, replicating a play that appears as the curtain runs. In this case they are presented with a man, a musician and the instrument ready to lead us to an ambiguous space between two-dimensionality and three-dimensionality. Musical and theatrical space, which is known to be very close to Picasso, through the esthetics that prepares for Parade ballet, where the costumes show characteristics that are in line with the work under study.

Its articulation as a creative manifestation, is articulated as a composition based on a common object (the violin case) that assembles two representations: a collage (papier- collés) and the pictorial cubist composition. Creating a dialectic between both techniques in a macro collage that could be considered a readymade ante litteram, far from the Dadaist concept, from the removal of the function that has the object in the daily use, the morphosyntactic destruction in favor of a new proposal formal and the recontextualization of the meanings that can be attributed to the object.

From its esthetic analysis it is possible to situate the work temporarily in the phase of synthetic cubism, specifically between 1914 and 1915. In this phase several elements are united and the unity of forms is recomposed, also recovering the colors, generating a synthesis of different investigations and figurative-sculptural results, which Picasso undertook at the time of synthetic cubism.

Although the work seems to be a unique piece in the artistic production of Picasso, due to the extensive work of the artist cannot be ruled out that he has made other compositions that may have similar characteristics.

Consequently, due to the characteristics compatible with the style, technique and materials of the experienced work, it is possible to indicate, from a historical-contextual perspective, that the piece features authentic characteristics.

39 Master in Arts with a mention in Theory and History of Art, Universidad de Chile. Degree in Art, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

40 Doctor (C) in Philosophy, Aesthetic Mention and Theory of Art, Universidad de Chile. Master in Arts, mentioning Theory and History of Art, Universidad de Chile. Graduate in Aesthetics, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

41 Specialist in cultural goods with mention in history and art, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy of the Università di Pisa.

42 Director of Veritart. See full CV in pp. 7-8 of the present file.

43 Martín, M. (s/f). Pablo Ruiz Picasso, in Museo del Prado. Recovered from: https://www.museodelprado.es/aprende/enciclopedia/voz/picasso-pablo-ruiz/f3cdd5d2-9564-42e6-a425-d11ffa7cd40c.

44 Ibídem.

45 Ibídem.

46 Widmaier, O.(2003) Picasso: retratos de familia, pp. 129-130. ALGABA Editors, Madrid.

47 Martín, M. Op. Cit.

48 Preckler, A. (2003). Op. Cit, p. 85.

49 Widmaier, O. (2003). Op. Cit. p. 132.

50 Ganteführer-Trier, A. (2006). Georges Braque. Pipa, vaso, dado y periódico, Cubismo, Colonia, p. 82. Taschen Editors.

51 Podoksik, A. (2011). Pablo Picasso, p. 148. Parkstone International, Nueva York.

52 Podoksik, A. (2011). Op. cit, p. 47.

53 Stein, G. (2016). Autobiografía de Alice B. Toklas. Penguin Random House. Grupo Editorial España.

54 Brodskaïa, N. (2012) Arte Naif, p. 28. Parkstone International, Nueva York.

55 García, C. (s/f). La presencia de la música en la pintura del cubismo sintético de Pablo Picasso hasta 1914, p. 9. Recovered from: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/cultura/web/html/sites/consejeria/publicaciones/Galerias/Anexos/musica -pintura-cubismo-picasso.pdf

56 Tinterow, G; Stein, S. (editores) (2010). Picasso in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 167. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

57 Read, H. (1966). The sculpture of Matisse, en Henri Matisse, Jean, L; Read H. Lieberman, S.W. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

58 Vallier, D. (1954). Braque, la peinture et nous. E C ’ , . 1, 1.

59 Foster, H. (2006). Arte desde 1900, p. 112. Akal Editions, Madrid.

60 Tinterow, G. y Stein S. Op. cit.

61 Foster, H. (2006). Op. Cit, p. 112.

62 Tinterow, G; Stein S. (editors) (2010). Op. Cit.

63 García, M. (s.f.). Op. Cit.

64 See images from 6.3 to 6.9.

65 Casas, N. (2012). Técnicas y secretos en Dibujo - Pintura y Restauración, p. 149. Bubok Publishing, Madrid.

66 Burgueño, M. (2009). Acuarelas, gouaches, pasteles y dibujos. Revista de Arte – Logopress. Recovered from: http://www.revistadearte.com/2009/03/23/acuarelas-gouaches-pasteles-y-dibujos/

67 Review the full results of the study in chapter 4 of this report.

68 Millán del Pozo, G (2009). Op. Cit, p. 185.

69 Duran i Escribà, X. (2011). Op. Cit, p. 56.

70 Bugliani, F; Di Lello, C; Freire, E; Polla, G; Petragalli, A; Reinoso, M; Halac, E. (2012). Op. Cit. 17 (2), 65-74.

71 Mayer, R. (1992). Op. Cit, p. 122.

72 Podoksik, A; (2011). Op. Cit.

73 See pictures 6.29 to 6.21 and compare the type of brushstrokes and / or similarity of the material used.

74 Preckler, A. (2003). Op. Cit, p. 90.

75 Ibídem, pp. 83-87.

76 García M. (s.f.). Op. Cit.

77 In picture 6.32 it is possible to appreciate a scene and part of the costume of the ballet Parade.

78 Aforementioned in González, J. (1986). Picasso sculptor. C ’ , XI, .6-7.

79 Cottington, C. (1999). Cubismo: Movimientos en el Arte Moderno (Serie Tate Gallery), pp. 59-70. Encuentro editions.

80 See and compare pictures 6.35 to 6.40.

81 Camarzana, S (8 de marzo de 2016). Un viaje a la escultura de Picasso, El Cultural. Recovered from: http://www.elcultural.com/noticias/arte/Un-viaje-a-la-escultura-de-Picasso/9023

82 Walther, I. F. (2000). Pablo Picasso 1881-1973. Genius of the Century, p. 46. Los Angeles, California: Taschen.

83 Tinterow, G. y Stein S. (editores), (2010). Op. Cit.

84 Harrison, Ch; Frascina, F; Perry, G. (1998). Primitivismo, cubismo y abstracción, pp. 95-98. Akal Editions, Madrid.

85 Temas Médicos (2003). Vol XVI, pp. 104-105. Bogotá, Colombia: National Academy of Medicine. 86 Harrison, Ch; Frascina, F; Perry, G. (1998). Op Cit, pp. 95-98.

87 Harrison, Ch; Frascina, F; Perry, G. (1998). Ibídem, p. 98.

88 Josa, L. (s/f). Juan Ruiz de Alarcón y su nuevo arte de entender la comedia. Universidad de Barcelona. Recovered from: http://www.biblioteca.org.ar/libros/200324.pdf

89 Harrison, Ch; Frascina, F; Perry, G. (1998). Op. Cit, p. 98.

90 See picture No. 6.57.